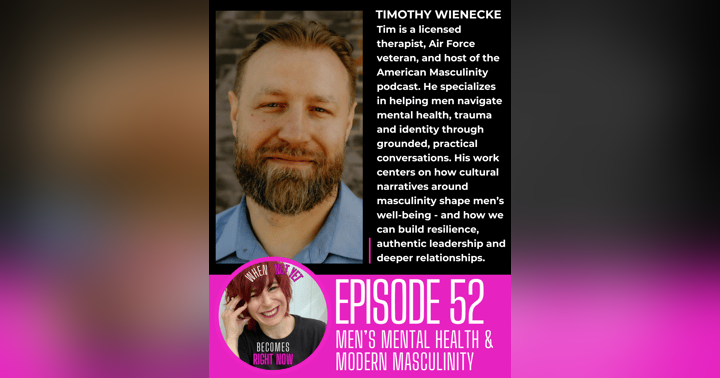

Men’s Mental Health and Modern Masculinity with Timothy Wienecke

Send us a text Jen speaks with Timothy Wienecke, a licensed therapist and Air Force veteran, about his journey from military service to mental health advocacy. They explore the complexities of masculinity, trauma and the societal pressures men face. Tim shares his experiences in victim services, the challenges of addressing sexual assault and the importance of community in healing. The conversation also touches on the evolving roles of men in society and the significance of diverse dialogues ...

Jen speaks with Timothy Wienecke, a licensed therapist and Air Force veteran, about his journey from military service to mental health advocacy. They explore the complexities of masculinity, trauma and the societal pressures men face. Tim shares his experiences in victim services, the challenges of addressing sexual assault and the importance of community in healing. The conversation also touches on the evolving roles of men in society and the significance of diverse dialogues around masculinity. Tim's podcast, American Masculinity, aims to provide a platform for nuanced discussions on these critical issues.

Key Takeaways:

- Tim's transition from military to therapy was driven by a desire to help others.

- Cultural narratives around masculinity significantly impact men's mental health.

- The importance of community in healing and personal growth cannot be overstated.

- Men often struggle with societal expectations of being providers.

- The role of men in society is evolving, with a focus on balance and connection.

- Diverse conversations about masculinity are necessary for progress.

Episode Highlights:

[02:24] Tim's Journey from Military to Therapy

[07:51] Cultural Narratives and Masculinity

[24:25] Work, Passion and Purpose

[27:25] The Burden of Masculinity

[30:01] The Role of Fathers in Modern Society

[44:28] The American Masculinity Podcast

Resources Mentioned:

The American Masculinity Podcast

Connect:

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCq0unI18LdfEqj0FJTvS-aA

https://www.linkedin.com/in/timothywienecke/

Go to http://www.mymoodymonster.com to learn more about Moody today!

Subscribe and Review Us on Your Favorite Podcast Platform:

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/when-not-yet-becomes-right-now/id1767481477

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/25eQxhfgLvdt3G9rY68AEQ?si=dc60122b6bc34484

Amazon Music: https://music.amazon.com/podcasts/2f6dece0-0148-4937-b33d-168b5aedf52a/when-not-yet-becomes-right-now

iHeart Radio: https://iheart.com/podcast/214320962/

Follow us on Social Media:

The When “Not Yet” Becomes “Right Now” Podcast: http://www.whennotyetbecomesrightnow.com

Instagram: http://www.instagram.com/notyettorightnow

TikTok: http://www.tiktok.com/@notyettorightnow

Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/notyettorightnow

Threads: ...

When Not Yet Becomes Right Now (00:00)

Welcome to When Not Yet Becomes Right Now, the podcast where we dive deep into the moments of transformation, the times when not yet shifts into right now and everything changes. I'm your host, Jen Ginty, and this podcast is all about those pivotal moments in our life journeys. You know the ones, when the hesitation fades, when we take that first step, even if it feels like a leap. It's in these moments that growth and healing begins. Each episode will explore stories of resilience,

moments of clarity, and the sparks that ignite real change. From personal experiences to expert insights, we'll uncover how people navigate the complex journey we call life and come out stronger on the other side. Whether you're searching for that spark in your own life or just curious about how change unfolds for others, you're in the right place. We'll discuss the ups and downs, the breakthroughs and setbacks, and how to embrace the right now, even when it feels out of reach. Because sometimes,

The hardest part of the journey is realizing that the moment you've been waiting for has already arrived. So take a deep breath, settle in, and let's get started.

When Not Yet Becomes Right Now (01:10)

Hello, this episode contains discussions of childhood trauma, sexual assault prevention, and mental health struggles, which may be sensitive for some listeners. Please take care while listening.

Jen (01:25)

Hello and welcome to When Not Yet Becomes Right Now. Today's guest is amazing. Timothy Winnocki is a licensed therapist, Army veteran, and host of the American Masculinity podcast. Tim specializes in helping men navigate mental health, trauma, and identity through grounded practical conversations. His work centers on how cultural narratives around masculinity shape men's wellbeing.

and how we can build resilience, authentic leadership, and deeper relationships. From soldier to therapist, Tim's journey is powerful. And today he's here to share what not yet meant for him and how right now came to life. Welcome, Tim.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (02:08)

Well, that was an incredibly lovely and thoughtful introduction. However, we're to make the soldiers mad when I was in the Air Force. So, ⁓ you don't got to be sorry. ⁓ But yes, slight difference, better food, better barracks, you know.

Jen (02:14)

I'm so sorry.

Okay, good to know.

So let's get into it. What is your origin story?

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (02:30)

Well, so the going from the Air Force into human services thing, I think, is a bit of a jump that a lot of people are a little confused by. ⁓ So I went into the Air Force later in life. I was 28 years old. For those of you who are old enough to remember, it was 2005. And out here in Denver, we had the crash early that everybody else had in 2008. ⁓ So I went in and I was already kind of everybody's uncle.

if that makes sense, right? I was about a decade older than the people I served with on average. And so people would look to me a little bit, right? Cause I was a safe person to go to, cause I wasn't a sergeant or anything just yet. But I was also old enough that people thought for some reason that 28 was wise. And when I got out into Korea for my first duty station, they do this thing in the military where when you show up at your first base, there's like a kind of a two week onboarding.

for the service, know, where they're like, hey, welcome to the Air Force. Here's all the different things on base. Here's all the different stuff to do. Here's all the different, you know, things that you might need. And in one of those briefings, it was for the sexual assault prevention folks. And in my class, it was primarily police officers, like military police. And so this woman comes in to do the briefing, which at this point, everybody's had this briefing.

like once a month, know, the Air Force is a really big organization and so whenever there's a problem, that's kind of what they do is they just do death by PowerPoint that you have to do and say that you knocked out every month or so. And so ⁓ the sergeant comes in and she's doing the briefing as we've all had at Nausium and particularly for the police officers, they have this briefing once a week and it's the same PowerPoint that they always have. And one of the guys puts his hand up very brashly, you he was 19.

seemed young. I like, man, not for nothing. I get this briefing at least once a week. Is there any way we can have a different conversation about this? And in the Air Force, you don't do that. You don't check a training sergeant. ⁓ And she got very, very angry. And she came at the room and said, if you'd stop raping people, I could stop giving this effing briefing. Sit down and shut up.

And so it was a room full of men that she was training. I think there was maybe one or two other women in the room. But at that point, you felt the room get really like hostile. Right? She basically just called every guy in the room a rapist. And, but we're all brand new, freshly minted airmen. And this is a sergeant. So everybody's like locked up in silent as she, you know, kind of angrily goes through the rest of her slides. And because of the silence,

I had a few minutes, right, where I think my initial response, probably like all the guys in the room, was angry, right? Feeling kind of attacked, feeling like I was being called this thing. But because I had that time, I was able to kind of look at her and see her a little bit better. And so she looked tired. She looked a little disheveled, which in the military is a big deal. You you look very crisp when you're in the military, particularly if you're someone that goes and gives briefings.

And it made me more curious than angry as to what was going on that this woman was this angry.

And so when the briefing was over, I took a look into it and found out that the base I was at at the time had one of the highest occurrences of sexual assault in the Air Force. And it's kind of because it's a, well not kind of, it's because it's a perpetrator's dream land. Most people only show up to the post for a year. It's a heavy drinking culture. So in Korea, in the bases, there's a tradition where when somebody new gets to the unit,

You sit them in a chair at the bar and you make them drink soju, is the local liquor until they can't get up.

And so between everybody being new, it being a first term base, so new airmen can go there right at a training and it being an 18 or ended up drinking culture. You know, if someone wants to be a perpetrator, it's a fairly easy place to do so.

But that made me want to do something about it. And that's when I volunteered and I became someone who you were allowed to report to. So in the military, if you're in uniform, the rule is you're a mandated reporter. Right? So kind of like I am, I am as a clinician. If somebody comes in and tells me that some kids are being hurt somewhere, I have to go to social services. And the military, if somebody in your unit comes to you and says, I was assaulted, you have to go to your command and tell them. Unless you're an advocate.

If you're an advocate, they can come to you and they can talk to you and it doesn't have to escalate into anything official if you don't want it to.

And so that's where I got my start and where I started hearing the stories of how people get hurt and what happens and started finding that I was able to hold that better than the technical work that I was doing. I was doing intelligence work, which man, the recruiters really get you. They're like, man, your job is so cool. I don't even know what you do. Turns out secret isn't always interesting.

But yeah, that's when I really kind of started to accept that my focus was going to be more on people than things, if that makes sense. And that was kind of the start of it.

Jen (08:07)

I want to touch on that 19 year old, kind of, that's the, that was the age, average age of the, the people who are coming in to serve. My son turns 19 next month and, oh, oh yeah. Okay. Yeah. No, this whole summer I've been on him. You need to be more responsible. You need to get ready for this and this and you know.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (08:18)

Mm-hmm.

So fully formed adult, ready to go.

Thank

Jen (08:37)

I, it's really difficult for me being on this end to see a 19 year old in that position.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (08:44)

Well, it's interesting. think 19 is a lot younger now than it was even 10 years ago.

Jen (08:52)

Yes, I agree with that.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (08:54)

Yeah, I think everything, ⁓ I think that whole generation compared, like I'm 45 and compared to my generation, they do everything about five to 10 years later to include their first date. Yeah, I think we've just made the world a little too safe.

Jen (09:12)

Sometimes, yeah, know, as a Gen Xer, my way of survival was getting a job. Also, I was living with an abuser, that was, yeah. So getting out of the house was the most important thing. So how do I do that? I get a job. And my sons probably didn't.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (09:15)

Mm-hmm.

Yeah.

I mean, that's an experience.

Jen (09:38)

really start working until they're about 18, 17, 18, whereas I was working at like 12. So I think there is that, there's a big difference there. I don't know if it's for better or for worse. I think that there were some pros and some cons to that in a sense that children get more of a childhood in a sense.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (09:41)

Yeah.

Yes, same.

Yeah, I

think there's something to be proud of in that we've made the safest generation of children in human history, but we've also made the most fragile generation in human history. think we, I think the ex-servicers and early millennials in particular, we were so kind of abandoned by our caregivers, even if it wasn't an abuse situation. You we were the latchkey kids, come home, make yourself a sandwich, watch TV. Nobody's there for you.

Jen (10:04)

Yeah.

Hmm, yeah.

Mm-hmm.

Well, it was the first generation whose parents both had to work.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (10:28)

Yeah, and it's not gone well, I would say. And so I think it's every parent tries to heal the wound they had for their children. And so, you know.

Jen (10:30)

Right. Right.

Yeah, sometimes.

think there's, I'd say I know I worked hard to do that myself, but I also see a lot of generational trauma that continued through because they didn't understand it and didn't speak of it. Now that we speak about it, it's become a little easier for us to understand we can make changes like that, right?

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (10:49)

Mm-hmm.

sure.

Yeah.

Yeah, I was a, like I'm a childhood survivor as well. My home was really chaotic. And my mother in particular was the person who made the life painful. And I know her story now. And she was a far better mother than her father was to her. Right? And I think...

Like there's kind of two perspectives that I clinicians talk about it in. And I think they're both valid depending on your story and what you need. Mine is most parents do the absolute best they can and absolutely love their children. It's just that their best is kind of trash depending, right? You you only know what you know, you only bring in what you're bringing. And like for my mom, you know, she was 19 when she had me, she was a baby. Like we were just talking about, right?

Jen (11:48)

Yeah.

Yeah, my mom had her first child at 19 too.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (12:00)

Yeah.

And so I, for me, it's been really healing to kind of have that grace from my mother. But I work with plenty of patients where that's, that grace is destructive because it was weaponized against them for a lot of the, a lot of their life. You know, the, person who hurt them would kind of play the victim card once they were old enough to be called out and say, you know, I did the best I can. You should love me anyway. You know, which

that's also not okay. You know, it's not a child's job to take care of a parent.

Jen (12:31)

Absolutely not, you're right. So did you decide to go further into psychology while you're...

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (12:39)

Well,

so that was a bit of a journey from there. So I'm in victim services at this point in Korea. I'm helping people as things happen. ⁓ It's complicated, right? Sexual assault is one of the more complicated crimes because everything in us, when it happens to us, is antithetical to getting evidence for a prosecution. Right? So when that kind of thing happens, everybody it happens to, they want to like go wash. They want to pretend it didn't happen. They want to minimize it.

And then over the course of a few days they realize they can't and they try to go report except now there's no evidence. And there's also, you know, most of the time it's acquaintances. It's people that you know and it's in an environment where there's plenty of consensual sex happening between parties. And so even if the guy's willing to, well, usually the guy, right, can't happen the other way, even if they're willing to admit that it happened, they'll say it's consensual, right? And so that all gets very ugly.

Jen (13:15)

the evidence is gone.

Yes, and that need to wash away that shame, even though you weren't the perpetrator. The perpetrator should have that shame, but it falls on the victim.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (13:47)

You know?

Well, I think that's the hardest thing about interpersonal violence. You know, when you get mugged by a stranger, it's scary and it's traumatizing, but it's not about you. When it's interpersonal like that, and it's that intimate, particularly with the most physical of intimacies, it can feel like it taints you, that it's now changed you. And a lot of it's just in how we frame it and the language we use around it.

Right? We don't say, like the language has changed a little bit, but it used to say, you know, like a battered woman, right? Like all of a sudden this happening now redefines their personhood as opposed to a woman who experienced, right? And I think that's why the survivor language has been so forthcoming and so useful for so many people, myself included. You know, it's a lot easier to identify someone who survived something difficult as opposed to someone who is surviving something terrible.

Jen (14:48)

And when I talk about my past, and I talk about my diagnoses, I say I live with complex PTSD and depression because at some point in my life, I switched it from I survived. And that was an important switch for me.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (14:56)

Thank

Mm-hmm

Yeah. Yeah, that's the one I think that, ⁓ when I do training for other clinicians now and I do trauma informed care stuff, it's, it's about making that transition. It's about making it part of your story because it's going to be part of your story. You know, that this is a fundamental event in your life and to pretend it's not, doesn't really do anybody any favors.

So from there, I went to England and England was a bit more challenging because I was on a very small base and I was the only resource. There wasn't ⁓ any kind of infrastructure for anybody going through those kinds of things. ⁓ And ⁓ because I was older, I kept getting handed, I like to say responsibility without authority. Right? I wasn't a sergeant. I wasn't an officer. I didn't have the official backing, but you

Jen (15:53)

Mmm.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (15:59)

You've got a college degree, you're old, you'll be able to handle it. And in big systems like that, having actual authority does matter, it turns out. But while I was there, I got really lucky in that the Air Force was a bit out in front of sexual assault compared to the other branches. I think in part because we had more women than the other branches. We're also, we tend to be a little bit more corporate in our culture than the other branches.

And so what happened to us is what happens to almost every organization when they start to take on a sexual assault problem, which is the minute there starts to be effective briefings on things, the minute it starts to be part of the culture that, hey, you know, that's not OK, reporting skyrockets.

Jen (16:45)

sense.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (16:47)

But it looks really bad in the news. And so the Air Force got in a lot of trouble. There were two drill sergeants that had been assaulting trainees, and there was a big scandal out at the Air Force Academy in the same year. I don't know if it's the same year, but they were really close together. And so that made the Air Force try to do something, which was great. They launched into a bystander intervention program. And so that's something that's just kind common practice now.

But back then, we're talking about 2010. And so they were ahead of most colleges in doing this program. And since I was in England and I was in a smaller base, I got to get trained on how to do the new training by the PhDs that developed it, which was really cool. Like just really smart, very passionate people. And one of them during the training for this pulled me aside for a lunch.

And she was like, hey, what do you do? And I was like, I do intelligence stuff. It's whatever. And she's like, yeah, you're doing the wrong thing. You should be doing this kind of work. And the way the training changed was fundamental. We went from doing a PowerPoint that just said, hey, did you know rape is bad? That you shouldn't do it. And if you do, these are the consequences for you. That doesn't really do anything. Anybody who's paying attention knows those things.

So instead, what the bystander training does, and anybody who's been on a college campus in the last 10 years has probably experienced some kind of education like this, where sexual assault is a violent crime. 60 % of all violent crimes happen in front of witnesses.

And so the idea that we're gonna teach women and men how to be safer in the world versus sexual assault has not worked. Women have been raised to think about the possibility since they were four. There's really not much more education that's gonna happen and like, hey, I know you've been thinking about this for your whole life, but let me just tell you this one tip and it's gonna make it all better. So instead, the conversation moves to how to notice when something might be happening.

how to care enough to do something about it for somebody else. And then giving people ways to do things. And so when I was working with Airman, it was great because they were kind of hard to convince, right? They're like, hey, it's none of my business. I don't know who that person is. If they're leaving the bar stumbling drunk, you I leave the bar stumbling drunk. Why, you know, I'm not gonna get involved. And so convincing them to like get involved, to check, you know, hey, it doesn't take much to ask somebody if they know each other. It doesn't take much to find her friend.

But the Air Force guys the minute that you convinced him that there was something they're like, okay, I hit him No, no, no, you're go to jail. Don't do that

Jen (19:35)

my goodness.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (19:36)

No,

no, don't do that. Talk to the bouncer, talk to the bartender, talk to their friends. Have one of your female friends go check on her, right? Like you take them through all the different things to do. And then all of a sudden, the barrier to action goes down because you have something you can think of to do, which for most people, we watch bad things happen in the world. And most people are pretty good people and they would like to do something, but in the moment, they don't know what to do. And so this lowers that bar to entry and it really, changes things pretty fundamentally.

So I finished up my five-year term in the Air Force and then got out and went to grad school for counseling. And I worked on the college campuses crisis center at that point. And I did the same kind of work except with college students. And that was a very funny cultural transition.

Jen (20:25)

I can imagine.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (20:27)

the folks on the college campus were much more likely to say, look, I'd love to do something, but I'm not getting punched in the face for a stranger. I was like, no, no, you don't have to get punched in the face. It's okay. Same solutions turns out, right? Go talk to the balancer, go talk.

Jen (20:36)

Total opposite, right? Total opposite of the airmen.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (20:46)

And so I think all in I did six or seven years of violence prevention work and advocacy work. And I'm really happy to have transitioned into clinical work. Advocacy work gets really hard because you always see people on their worst day. When you're working a crisis line, everybody that calls in, it's one of the worst days of their life. And then you hand them off to resources and you never hear from them again. You don't know what happens. You don't know if they get better.

just get to hear them on that day. As a clinician, I get to hear the whole story, sometimes, not always. People sometimes come in and leave, but for the most part, I get to see people's journey and that refills the tank a lot more.

Jen (21:34)

So you get out of the military and you start your own clinical, did you become a psychologist? you, what did you?

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (21:45)

Well, so it

was a, so the program to become a licensed counselor was three years. And so during that three years, the first year I did most of my work with the crisis center. And then I transitioned over to working for the veterans services center and I built out a veterans transition program. And we went from like two people helping, you 20 or so veterans that came into campus to, I had a volunteer staff of 25 and.

of the thousand students that were starting as veterans, they all got paired with a mentor and had an orientation. And I built all that and it was really, it was really wonderful. And I think it was really nice to kind of have a bit of an off ramp from the advocacy work to the clinical work, right? Because the problem with clinical work is I'm touching people one at a time. So helping societal change is more difficult. And sometimes you get a little bit, you feel siloed.

I know the person in front of me story, I know I'm helping them and these problems are still widespread in the world and there's only so much I can do. But it was really just powerful to the whole time be in people surfaces, right? Like helping people, helping things move. And so I did my internship at a pretty popular trauma clinic out here at the time. It was really competitive to get in.

and learned how to help some of the most horrendously hurt people that you can imagine. To this day, I've been doing this almost 10 years now, and my most complicated cases still happened in that clinic, because that's how our system works. We put the most at risk and the most at need in front of our most junior and most inexperienced. It's just how money works, unfortunately. But I learned a lot. I learned how to clean up things, how to help people.

how to give some structure around things that need structure. And then after all that, I decided I never wanted a boss again. After the military and after working on college campuses and big organizations, don't get me wrong, like running your own practice, there's plenty of mistakes to be made, but at least they're mine and I get to clean them up. I do miss vacation days though, if I'm being honest.

Jen (23:57)

Exactly, the entrepreneur's life.

True, true, yeah, they're few and far between when you are an entrepreneur.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (24:10)

Yeah, but it's, ⁓ I'm very, very lucky. I work primarily with men now. so career counseling is a big part of my work. Every guy in America, the first question they get asked anywhere they go is, what do do for a living? Right? It's an important distinction in question. And it's really hard because most people don't get to find work that matters to them. And I think it really hurt the exers and early millennials because that's what everybody told us to do.

The myth was, go find what you love and then do that for a living and you'll never work a day in your life, which is a total nonsense. It means I'm going to work and basically almost kill myself working so hard because I love this. Oh wait, that didn't work out at all.

Jen (24:48)

Absolutely.

I felt that way about my first like 10 years of working because I did learn pretty soon that I didn't like having a boss. But the Gen Xers, like a nine to five is the correct way to live your life. And the same was with my mother. My mother does not believe that I have a job.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (25:01)

Mm-hmm.

Yeah.

Nevermind that you've make your mortgage just fine.

Jen (25:25)

Right, right, exactly.

But that is, it's very interesting how we've, again, another change in generations where people are now deciding that they are going to do what makes them happy.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (25:39)

what I like about the young people I work with is they're a lot better at accepting the balance of work and passion than we were raised with. And a lot of the times for the guys I work with, Denver's a big tech town. I work a lot with tech guys. Most of those guys aren't passionate about what they're doing. They're just figuring out a way to make money with something they're good at. And by acknowledging that that's not going to be their passion, they end up being so much better about work boundaries.

They find a job that pays them enough, that respects their time enough that they can go do the volunteering. They can go coach their kids' sports team. They can go be the dad they want to be. They can go work for that nonprofit on the side if they want to, but their mortgage is covered, their rent is covered. And that just, it's feeling so much more whole to me as a society. takes the pressure off of your passion having to be your work.

Because I think for a lot of people, their passions, once it becomes work, it kills the passion.

Jen (26:38)

Yeah. I think passion and purpose are two different things. When I realized what my purpose was, when I created my moody monster, I created this doll that you can rip apart, get all your frustrations out on, I realized that it was my purpose to get them out into the world, to share them with the world. And it also can be my passion, but I can also have other passions that I want to do.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (26:42)

It's true too. It's true too.

Yeah.

Yeah,

yeah. Yeah, it's, I think everybody finds their thing if they find some happiness, right? They find some purpose and they find some passion. I think where a more fulfilling life happens is when we recognize that those change over time too. Like on the other end of the spectrum, I get these guys that used to love what they do.

Jen (27:07)

Right?

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (27:32)

And now it's crushing them and they just feel so hopeless. Well, I found my thing and now it's awful.

Jen (27:41)

Yeah, I've spoken with people before about how they had the mentality of it's better to look good than to feel good. And it doesn't matter if you love your job, you're making excellent money, you're taking care of yourself, but there's still an emptiness.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (27:49)

Mm.

Well, and I'm actually working on a book on this right now. So if the idea is half-baked, forgive me. But it's something that other people have written about as well. The idea of a provider for men has really hurt us overall. Not because men shouldn't provide, right? Like if you're talking about a family unit and someone providing, that's great. But we made it the only rule.

Jen (28:04)

⁓

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (28:28)

And we basically said, hey, be a provider. We don't need dad. Right. Go work, come home, go in your study and shut the door unless the kids need a spanking or go to work, get divorced and then don't have custody and don't see your kids. Right. And so even now guys still have that story of like, if I'm not a provider, I'm not a man. And so it's not even as much, you know, look good over feel good. It's this myth that

I'm supposed to sacrifice my happiness to be a provider. I'm supposed to give that up. That's what a man does. And we don't have to. We can find balance. We can find a way to be a provider and dad. Or a lot of women have more earning potential than a lot of guys right now.

Jen (29:16)

Yeah, there should

be equality to it.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (29:19)

Well, that was the dream of feminism, right? Is that everybody gets to choose and for better or worse, right? Women now have the choice to be everything, which means you all have to be everything or everybody judges you for everything, which is not the best. And I think this, ⁓ it's awful. It's ridiculous. And now it's the, I feel like this is our first real generation of guys where when a couple has a kid, there's an actual discussion over who stays home. And that's still not.

Jen (29:21)

Mm-hmm.

Yeah, that's the pressure.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (29:47)

Guaranteed, but it's starting to happen

Jen (29:50)

And that's progress. Yeah.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (29:51)

think so.

There's a guy named Richard Reeves, put out a book called Of Boys and Men, Why They're Struggling and What to Do About It. And he advocates for the idea of if it's a two working household of a mutual slowdown. And that's what I try to guide my patients towards is, you you can push one thing in your life at a time.

And your kids, 95 % of the time you spend with them in their entire lifetime happens before they're 18.

And so taking a career pause while your kids are little. You know, I'm not saying you got to like stop working entirely, but maybe hold to that 40 hour week. Don't chase the promotion. Right.

Jen (30:38)

Women are supposed to be the ones who write down the history of their children. And many times the fathers don't get the chance to be a part of that.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (30:47)

Yeah, it's been one of my favorite things about the work. I never expected our dad's generation to show up for therapy. Like the John Wayne guys, those guys weren't gonna come to therapy, right? They do, turns out. I get a few. And what I love about working with the ones that have grandkids is how healing that is for them. Because most of them under their, you know, in the nougat of the outer, like, I'm a provider, did good, right? They missed it.

Jen (30:55)

Mm-hmm. ⁓

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (31:19)

And they know they missed something. And so by being around and letting down the idea that they're not supposed to like the kids, letting down the idea that it's not okay for a grown man to like it on the floor and play with a three-year-old, right? All of a sudden, that's where the fulfillment comes for them later in life. They really struggle once they lose their jobs. Like retirement, the way that Boomers framed out retirement was terrible.

which is the end of labor

not the end of labor for money. Right? I think as humans, but men in particular, we need labor. We need to feel like we're doing something that's contributing to the wellness of the people we care about. Right? And so since for so long, our only avenue to that was professional. Once these guys lose that, they were listless, they were depressed, they were angry, they were suicidal. And so by convincing them that their labor can be

You can be the afternoon care for the grandkid. You can be the person that does these things. You can be the wisdom in your family and that has value. It's really healing for so many people.

Jen (32:33)

I can imagine. I've witnessed many times, my friends will say, my parents stopped working and now they do nothing. And the plasticity of their brain has, yeah. And how sad that can be to watch as well as it happening to you. Because when we look at our parents, we're like, they're the ones who...

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (32:42)

Mm-hmm.

goes away. ⁓

Jen (33:00)

did the things. They got the things done and then to watch them kind of mentally decay.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (33:08)

a little bit. it's funny, the ex-her grandparents that I work with, I think have the hardest time. Because they're like, look, I raised me, I raised you. Can I be done for some portion of my life?

Jen (33:20)

That could be valid.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (33:22)

Right? And I think where we get lost, so America is the most individualistic culture on the planet. And that has a lot of good things to it, right? We tend to be better at business than people. We made it to the moon. Our Star Spangled Banner is like the only trash talking national anthem in the world, which I think is amazing. Right? We're better than you, we're better than you. ⁓ It's ridiculous, but it's awesome. On the flip side of that though,

Jen (33:42)

Hmm. Yes!

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (33:51)

We undervalue community tragically.

And I think that's where like the Xers got so lost, right? They were so like used to being alone. Right? We got so used to being in these little isolated bubbles that we feel safe in them.

But like we were talking about with your son, safety is not always where growth lives.

Jen (34:15)

Right. And community always comes up for me in these talks. And I hated community when I was younger. If I had to go to, right, if I had to go to group therapy, it was the worst thing in the world. All I wanted to do was leave and get a cigarette and, you know, just sit outside. And we were forced to sit together and talk about our problems. But now,

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (34:25)

Because it was used to hurt you.

Sure.

Jen (34:45)

as an adult, when I finally realized that I had to get on this journey, community became such a big thing for me because I did realize that there are others out there who have gone through similar situations and have similar ⁓ diagnoses or that they understand.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (35:08)

Yeah, I think there's a powerful place for being around people you identify with. I think though, we prioritize that too much. Like, have you ever heard of the book Bowling Alone? It was written in the 80s.

Jen (35:23)

I've heard of it, I don't know much about it though.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (35:25)

It's a good book. And the man who wrote it basically predicted Trump and not Trump specifically, but this situation. And the reason why it's called bowling alone is because up through the seventies, bowling was a league thing. Bowling was like, it was super popular. Every middle-class family played it and you played with your neighbors. So if you were a liberal professor and your neighbor was a construction worker, you played on the bowling league together. You sat in a literal circle one night a week and

Jen (35:29)

⁓

Okay.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (35:54)

bullshit over beer, right? And then in the 80s, for some reason, all of sudden people started bowling by themselves and the leagues kind of went away. And everybody kind of retreated into their homes and these silos. And it makes us forget that community doesn't mean you have to like everybody that's there. Community doesn't mean you have to agree with everybody that's there. All community means is that we're moving towards something similar, whether that's, you know, we both work at the food bank.

Jen (36:17)

Very true.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (36:23)

I'm a agnostic guy. Church makes me uncomfortable for a lot of reasons. But when I go volunteer at the food bank, you better believe that one of the guys I really like there is Mormon and incredibly involved in his church. Right? And we have a great time.

Jen (36:40)

Yeah, I think that's really important what you touched on, that we don't always have to be in cahoots with everyone that could be in our community. When you have tight friend circles, you tend to agree on pretty much everything. Like my friends that I had all the way from college, like we've been together 30 years. And yeah.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (36:49)

Yeah.

That's lovely. I'm so glad you have them.

Jen (37:06)

Yeah, you know, and one of them's getting married again and we're going, we're all going to be walking down the aisle as bridesmaids again, you know? Yeah, exactly. ⁓ But that group is insular. There's also a bigger community that people can get themselves involved in and feel good about it.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (37:12)

That'll be fun.

Yeah, it's interesting. Someone pointed this out and there's good data behind it. I'm a really liberal guy, right? ⁓ But I often dislike how liberals treat people who make mistakes. Right? Like with liberals and with the idea of all the online chat rooms for the younger people, like the discords and such, they're great. And I think we need to kind of balance this out where

Jen (37:34)

Me too.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (37:55)

particularly those of us were hurt so badly like you and me, we needed some space with people that understood before we were ready to reenter a larger community, right? But I think now they don't leave. They get into the little community of people that are exactly like them, that believe all the same things they do. And then anytime anybody disagrees or makes a big enough mistake, they're out.

Jen (38:06)

Yeah.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (38:25)

and they're completely ostracized. And with conservatives, they've got their things that they're very upset about and they've got their things that they will ostracize you from the group for, but you can always come back. You know, the redemption arc for Christianity is huge, right? And don't get me wrong, you might not want to go back with the stuff they want you to sign on for, but I wish we had a little bit more of that in liberal circles where, know, hey, I made a mistake.

Jen (38:27)

That's the rub.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (38:55)

I'm learning. Like if I held the same beliefs now that I did at 20, I would be a terrible human being.

Jen (39:01)

yeah, again, going back to that age, we're not adults.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (39:07)

Well,

it's just times change, right? Like, I got an allyship award from the LGBT office on my college campus because I helped them make the office, right? And this was, I think, 2001.

I'd never met a trans person, right? I had no concept of what that was like. Back then you couldn't be bi, right? If you were bi, people were very uncomfortable, like pick a side kind of stuff, right? And now the idea that someone would be ostracized by who they're attracted to is kind of ridiculous in most circles. Like even in conservative circles, they're not as concerned about whether you're gay or lesbian anymore.

They've got a long way to come on trans stuff. But we had all those, what was it, like in the 2000s, all those cranky old white Republican senators who were like, well, I had this cousin and it was a wedding and it was a beautiful wedding. I guess it's okay. Right.

Jen (40:03)

I guess it's okay.

If a relative did it, then maybe it's okay, I guess.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (40:09)

Well, and so I think

like we need to accept that there's some truth to that, right? We people are uncomfortable stepping outside of their normal. And it's how we end up hurting ourselves. Every patient I work with, when they come in and the pain they're in, their pain is normal. And we will almost always default to knowing what happens next, then taking a risk for hope.

And so it takes outside exposure. It takes someone that matters to you experiencing something for it to become real in your world. And I'm not like, I wish more people had more empathy and just because someone said, Hey, it's hurting me. we do something different? Would be enough. I sincerely wish that was why we did things, but it's generally not. It's usually because you finally witnessed something like I, ⁓ I've had

This kind of situation happened to me five times in my life now where I held a wrong belief. So I grew up outside of DC and my school was really diverse and I got beaten for being a white kid. And I mean properly beaten, like bruised or cracked ribs beaten. And my mom's family was Southern and were very, very like overt racists. And so my takeaway from that at 19 was racism is nonsense.

It's rich people trying to get poor people to hurt each other, which is also true. Right. That's why it's like largely enforced. But I was a loud, brash, you know, white 19 year old who's used to filling space. Right. So I'd argue about it in classes. I'd be in sociology classes and arguing about the, you know, the issue of racism and what it is. And these very patient professors and ⁓ nice people dealt with me being very. Like expressive of that.

And then one day I was in line for a coffee at Starbucks and I was wearing my poor kid outfit. Like I had moved in with a family to go to college that were fairly well off, but I grew up pretty poor. And so I still dressed like my identity was still poor, right? And so I like had my cutoff jeans. I looked like I could rob the place, right? I'm in a Starbucks, but I don't look like I belong in a Starbucks in 2000. And in front of me, there's a petite, incredibly well-dressed, like a business suit woman who's black.

And the barista, who was this very sweet kind of, you know, 20 something college student working at a Starbucks, looked right over her at me and asked me if what I wanted, like asked me for my order over her. And I said, no, no, she was here first. And the barista was like, my God, miss, I'm so sorry. I'm so sorry. What would you like? And for whatever reason, that was the moment.

that all those other things that people had been telling me cascaded in. And it's this surreal, and I'm sure a lot of people can relate to this, where you hear the final thing you need to hear or see, and then you just go back to all these inflection points that were all of these other opportunities that you could have learned that. And for me, like at 20, I felt terrible. For months, I felt terrible. Now in my 40s, the last one I had was two years ago.

Jen (43:06)

Mmm.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (43:31)

And now I'm a lot more like forgiving of myself for it. Like I'm curious, I do my best. And when those moments happen, I make amends. I take accountability if I need to where I can. But people change and people, you let them, they change for the better.

Jen (43:49)

Yeah, and that's the healthy way to do it, right? But we're not taught that healthy way.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (43:53)

Well,

no, and it's so hard because there's so many people doing so much to hurt people. And so I don't really expect...

like a trans person to be forgiving and a cis person who's being kind of crap about trans stuff, right? They're being victimized. But another cis person being like that unforgiving for someone who held that view when they changed their mind, I think that's cruel. Like if you're over 25 and you've never changed your mind, you're doing it wrong.

Jen (44:35)

That's growing up.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (44:37)

If you do it right.

Jen (44:38)

Yep. Yeah. So tell me about the American Masculinity

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (44:43)

podcast.

Yeah, so ⁓ remember how earlier on I was like, yeah, as an individual therapist, we only get to see one story at a time? Well, I'm pretty popular in my area. And there's a lot of guys that I have to say no to, that try to come in. Because in the counseling field, four out of five clinicians are women. And so there just aren't a lot of people that are masculine that are in the space.

And all the data we have on counseling is you tend to have a better experience if the person sitting across from you looks like you. All right, that's just across the board, doesn't matter who you are. And so I got kind of tired of those guys not having a resource. And the conversation has shifted around masculinity. Up until very recently, if someone was publicly speaking about masculinity and helping guys out, they were pretty men's rightsy.

and often veered into blaming women for all the ills of men, which is garbage. And it's been nice because now there's more more voices for guys saying, hey, no, men are struggling. And yes, women and trans and non-binary people are struggling, and we absolutely should be addressing that. But did you notice that only one in three college students are boys?

Did you notice that boys are twice as likely to be expelled for the same offense as girls in school?

Did you notice now that we've kind of leveled the playing field of school, that boys who need activity to learn are falling behind because schools don't provide activity?

Jen (46:15)

very true.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (46:18)

And so those conversations are now happening and they're very important. And I wanted to be part of it. I wanted to bring that expertise. And I think I have a unique background for it. You know, I've got numerous allyship awards. I've worked on interpersonal violence for a large part of my career. And I've spent the last, you know, almost 10 years working almost exclusively with men on men's issues. And so the podcast is a space for a more nuanced conversation about the topics where I get to, it's kind of fun for me because I get to geek a little bit, right?

I get to find very smart people and very dedicated people to their thing and bother them for answers about the thing, which is the best. It's the absolute best, right? and it's been, it's been really lovely. The episode, that released two weeks ago, I'm really proud of. ⁓ I was able to find a black lives matter advocate to come on and we talked about what white guys need to know. And I'm out in Denver. There's not a lot of opportunity to have a black friend. I've got one.

I'm not bothering him with this. He's got a lot of white guys bothering him for this. He doesn't need it from me, right? And so Martin came on and we had this great conversation and he was honest, but he was very direct and it was lovely. And I got to ask like curious questions of like, Hey, when I do this, how bad is that? Right. How can I do better? Right. But you just don't have an opportunity. Most of us have friends that look like us. That's just kind of how we organize in most places. And so I'm really excited to kind of bring those conversations forward and provide them for

Jen (47:33)

We all wanna know. Yeah.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (47:46)

people. It's a lot of fun.

Jen (47:48)

Yeah, I feel like the podcast for me really connects me with not just like-minded people, but diverse people for me. know, I myself have religious trauma and I tend to have people on that talk about religious trauma, but I also do have people on that talk about their faith. And I believe that

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (48:15)

Yeah.

Jen (48:18)

Faith is extremely important for our mental health. Having faith in something.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (48:23)

It really is. It's really unfortunate for me since I don't have it. It annoys me. But by all metrics, if you have religion, you live a happier life on average by a significant amount.

Jen (48:35)

Yeah,

I'm not religious, but I do have my ideas of what is a part of our universe. I guess you could call it spirituality, but there are, and then the times that I didn't have faith, those times were the lowest for me. Yeah.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (48:45)

Yeah.

Yeah, they get dark. They

get dark. I think it's hard to sit in the existential dread of all we have is what we see. Yeah. And it just doesn't make sense. I don't know. think to be an atheist, you got to work really hard at that to prove it, to prove a negative, right?

Jen (49:05)

Mm-hmm.

Yeah.

I think proving the negative is always the hardest thing to do. ⁓

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (49:19)

Some would say impossible. ⁓

Well, and I think like I think we're of an age and so in the 90s and 2000s to be an atheist meant you were bothering people. Right? These were these were the guys that were like, no, let me tell you why your faith is stupid. And I've just never been that angry about it, you know, so it just didn't work. agnosticism works really well for me. Like, look, I don't have the ego to think I understand whatever it is. I just know something's there.

Jen (49:31)

Hahaha

Hahaha!

Yeah, yeah, and that's really important. It can make the difference in your life, especially if you're in a depression.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (50:00)

Well, to be honest, for me, it helps me celebrate the good times. You know, it's a lot easier to see the bigger light in the world when your life is going well. And you need to see the light while it's there because eventually it's not going to be. And you're going to need to remember it to get back to it.

Jen (50:18)

Yeah, very, very true. Well, Tim, where can we find you?

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (50:24)

you can find me at americanmasculinity.com. Keep it pretty easy. ⁓ and I will give you a link. found one of those little link tree things where it's one link that lists all my stuff. So, ⁓ and then I'll take you to the podcast. If you want the podcast. I also have developed out some free tools for guys that can't get to therapy. They won't replace therapy. I want to be really clear. Like you need a clinician for clinician things, but you can also generally make your life a little bit better with some simple things sometimes. And so that's what those are.

Jen (50:32)

Yes. Yes.

Yeah.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (50:52)

And then if you're in Colorado and you need some counseling and you're a guy or you have a loved one that's a guy that you're looking to send somewhere, ⁓ my counseling services are listed there as well.

Jen (51:01)

Wonderful. Well, thank you so much, Tim, for coming on the show. This was such a great conversation.

Timothy Wienecke, MA, LPC, LAC (51:07)

Thanks so much for doing what you do and bringing so much joy into the world.

Jen (51:11)

Thank you so much.

When Not Yet Becomes Right Now (51:16)

Thank you for joining us for this episode of the podcast. This show is produced by Phoenix Freed LLC and I'm your producer, Jen Ginty. We hope you found today's conversation inspiring. Thank you for joining us for this episode of the podcast. This show is produced by Phoenix Freed LLC and I'm your producer, Jen Ginty. We hope you found today's conversation insightful and inspiring. If you have a story of your own about when a not yet moment became right now,

We encourage you to reach out and share it. You can find more information about being a guest on our show at whennotyetbecomesrightnow.com. Remember, you are not alone on your journey, whether it's a journey of healing, growth, or transformation. Every story matters. Thank you for listening, and we'll catch you next time with another inspiring episode.